Verbal Validation for Kids is More Than “Good-Job”

By: Sasha Pipke

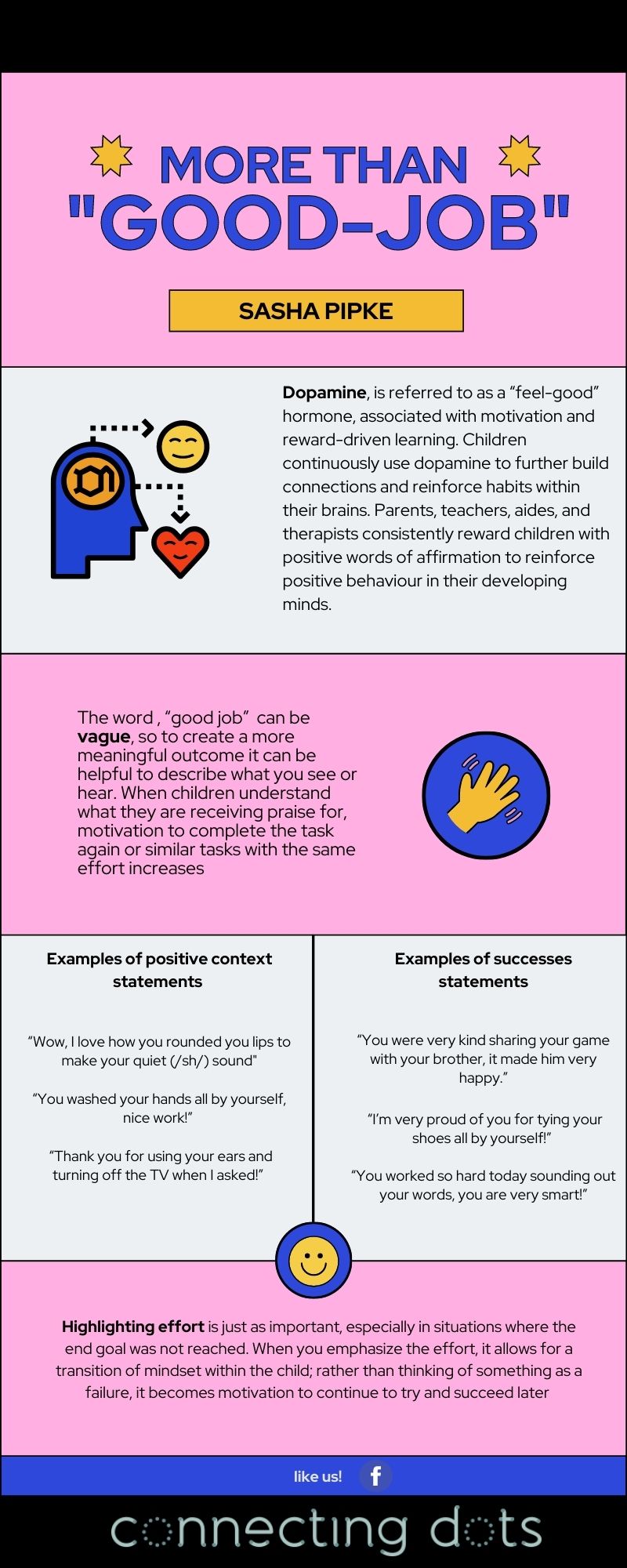

Dopamine, also commonly referred to as the “feel-good” hormone is associated with motivation and reward-driven learning. Dopamine allows for a positive sensation released in the brain that motivates future actions, allowing for a similar release of the hormone (Bogacz, 2020). Children continuously use dopamine to further build connections and reinforce habits within their brains. Parents, teachers, aides, and therapists consistently reward children with positive words of affirmation to reinforce positive behaviour in their developing minds. This motivation is known as extrinsic motivation, where the child receives external validation and praise, as opposed to intrinsic motivation (which involves of self-encouragement). The choice of words used by adults plays a critical role in the child’s motivation. We often resort to saying “good job” to further validate the actions of others, yet this phrase is an overgeneralized blanket term, used regardless of the task at hand. Although this seems like the perfect phrase to continue to motivate the child to perform a task, it lacks meaning and does not specifically recognize accomplishments. We must ask ourselves, therefore, how can we change our vocabulary to motivate children in a meaningful way?

As we know, “good job” is ambiguous and vague, so to create a more profound and meaningful outcome it can be helpful to describe what you see or hear. When children understand what they are receiving praise for, motivation to complete the task again or similar tasks with the same effort increases (Schwarz,2018). It’s important to still use vocabulary that the child understands and can easily understand in a positive context. Some examples are:

- “Wow, I love how you rounded your lips to make your quiet (/sh/) sound!”

- “You washed your hands all by yourself, nice work!”

- “Thank you for using your ears and turning off the TV when I asked!”

Additionally, it is important to provide children with the success of their actions. This allows you to provide extrinsic motivation in a way that will allow your child to also feel intrinsic motivation. This can be done with personalized ‘you’ statements that place ownership on the child for their own actions. Some examples are:

- “You were very kind sharing your game with your brother, it made him very happy.”

- “I’m very proud of you for tying your shoes all by yourself!”

- “You worked so hard today sounding out your words, you are very smart!”

Lastly, it is important to highlight the effort, especially in situations where the end goal was not reached. When you emphasize the effort, it allows for a transition of mindset within the child; rather than thinking of something as a failure, it becomes motivation to continue to try and succeed later. Goals do not happen overnight, and children should not expect that everything they do will be accomplished at the same rate.

Saying “good job” has become hardwired to address success in children, however, it does not carry substantial meaning. Changing our vocabulary to better highlight children’s effort and success is a small change that can make the word of difference regarding self-praise and motivation. This change in vocabulary will not happen immediately. Try to first notice in a week how many times you say “good job” then try to replace a few “good jobs” with a specific validating phrase and continue to progress from there. You’ve got this!

References

Bogacz, R.(2020). Dopamine role in learning and action inference. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53262.

Corinne. (2019). Why You Should Stop Saying Good Job and What to Say Instead. The Pragmatic Parent. https://www.thepragmaticparent.com/stopsayinggoodjob/.

Schwarz, N. (2018). 50 Ways to Say “Good Job” (Without Saying “Good Job”). Imperfect Families. https://imperfectfamilies.com/50-ways-to-say-good-job-without-saying-good-job/#:~:text=Author%20Alfie%20Kohn%20talks%20about,reduce%20their%20sense%20of%20achievement.