Effects of Stress On The Brain

Effects of Stress On The Brain: How stress can affect the human brain in different stressful situations

By: Maryam Abro

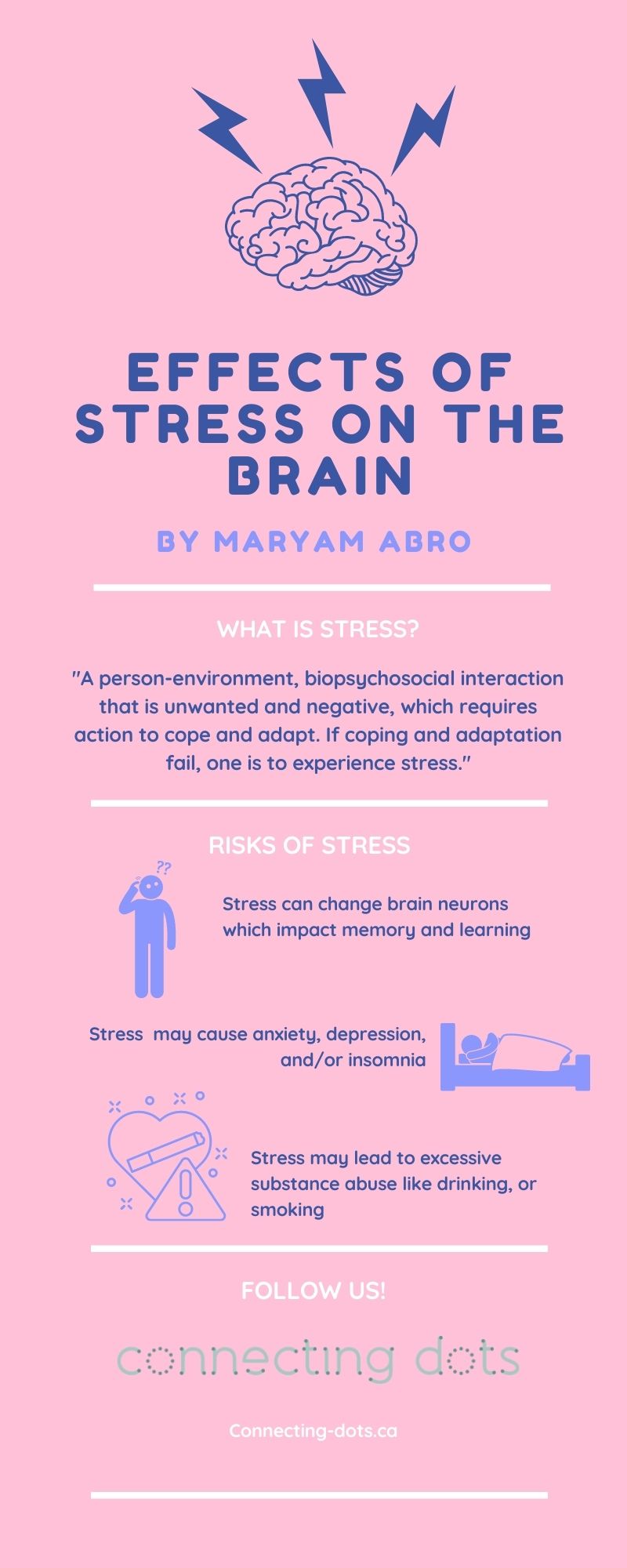

To understand the common feeling of “stress” on the human brain, we need to understand the definition.

Carter (2007) defines stress as:

“A person-environment, biopsychosocial interaction, wherein environmental events (known as “stressors”) are appraised first as either positive or unwanted and negative. If the appraisal is that the stressor is unwanted and negative, some action to cope and adapt is needed. If coping and adaptation fail, one is to experience stress reactions.”

Stress is a result of uncertain, adverse, random, and overwhelming events. Stress is greater if there are already problems and struggles in one’s life. Stress reactions arise regardless if stressors are “objective” or “subjective” and long-term exposure can result in negative psychological consequences, ranging from mild to severe.

It is believed by Carlson, (1997), that people who are experiencing severe stress react in one or more of the three fundamental reactions that are presented by one or more “physiological, emotional, cognitive, or behavioral modalities. The core reactions are:

- Intrusion or reexperiencing

- Arousal or hyperactivity

- Avoidance, or maybe even physical numbing”

Unfortunately, stress is a word used frequently in modern-day society, often used to describe the experiences that cause anxiety and frustration because they make individuals feel insecure and leave them with the feeling that they wouldn’t be able to successfully cope with situations that they may be facing.

Nowadays, there are many different stressors, especially during the Covid-19 global pandemic. Some of the stressors that may occur due to Covid are new rules causing changes and making new normal for individuals, social distancing, problems at an individual’s job or home, financial worries, etc. It is certain that these stressors would be, or have been deeply amplified due to our current circumstances with Covid-19 as well. Sometimes, these stressors can have serious implications, for example, effects of social distancing and isolation on mental health, loss of livelihood because of shutting down businesses, deaths caused by drugs and alcohol during the pandemic, increase in domestic violence, etc. Also, they may trigger the human “flight or fight response”. Besides creating daily annoyances in life, these stressors can lead to chronic stress, or maybe even PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), which is an aftereffect of a tragic experience.

The life experiences described above are the most common stressors that trigger human beings and cause their behavior to change in a certain way. For instance, being “stressed out” may create anxiety and depression, insomnia, and excessive substance abuse like drinking, or smoking. Some individuals may even resort to using medications such as “anxiolytics”, benzodiazepines, and sleeping pills to get rid of stressful thoughts. The prolonged use of such self-medication can result in various negative health outcomes.

The human brain itself is responsible to select the experiences that cause stress and it also categorizes the behavioral and physiological reactions to the stressful events, which can promote or deteriorate health. Acute and Chronic Stress has been shown to cause changes in the brain and affect many systems in the body like “neuroendocrine, autonomic, metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune”.

As discussed earlier, it is well believed that stress causes changes in the brain. Now, the question at hand is: what Kind of change does stress cause in the human brain? To find out what kind of changes take place in the human brain, we need to explore the effects of stress in different parts of the brain.

Extreme Acute and chronic stress may cause effects on the amygdala’s stress response through three core regulatory systems: “the serotonergic system”, “the catecholaminergic system” and the “HPA axis”.

The advancement of brain imaging techniques has enabled researchers to examine the neural circuit activity changed by acute stress in humans. MRI studies have revealed that the subjects who listened to stressful events related to their life had increased response of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) in the medial PFC (anterior cingulate cortex), particularly in the right hemisphere indicating the anterior cingulate cortex’s part in processing mental suffering. Studies conducted on humans also reported how drastic stress affects the dlPFC operations, participants who had been exposed to stressful videos, displayed poor performance of N-back working memory, and reduced BOLD activity over dlPFC. Results also revealed that severe stress ended the normal deactivation of the default mode network. The subjects who had greater levels of catecholamine had more stress causing damage to working memory performance and reduction in dlPFC activity. There is a correlation between stress-induced catecholamine release and poor working memory performance. Exposure to unmanageable stress and higher catecholamine levels together impair the higher cognitive functions of PFC.

The hippocampus performs some of the higher tasks in the brain, such as encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Once it receives the messages from the axons, this information is processed through different synaptic mechanisms. The hippocampus sorts out the information and differentiates between important and less important information. Exposure to acute stress makes the hippocampus open to attack. Minor and short-duration stress normally increases hippocampal operation by increasing “synaptic plasticity”.

Stress impacts learning and memory tasks in humans and animals by changing the structure of hippocampal neurons . These alterations occur in different stages, starting from the changes in the synaptic memory to the changes in the dendritic branches . Most drastic effects of long-lasting stress on the hippocampus is a decrease in the pyramidal cell dendrites branches. The amount and form of “synapse-bearing spines” are active and are controlled by “factors including neurotransmitters, growth factors and hormones that, in turn, are governed by environmental signals, including stress”.

The information discussed above highlights some of the crucial structures of the brain and their response to stressful events. Many other areas need to be examined in this connection, such as loss of synaptic connections, dendrites, spine and “the generality of the stress response to other high-ordering association cortices, and how genetic insults interact with stress signaling pathways to hasten disease”. Stress and its effects on the brain is a vast area of research. The crucial point for future research is to unravel how different mechanisms few of those mentioned above (CRH, neuropeptides, neurotransmitters) respond to stress hormones such as adrenal and stress-associated neurotransmitters. It could be a challenging task to study the joint role played by these mechanisms to alter the hippocampus in response to stress. Further research would be required to uncover some of the effective treatments and helpful approaches to handle the drastic effects of both acute and short-term stress.

Tablet Tantrums

By: Crystal McNaughton

Does your child turn off the screen/IPad/tablet when you ask? How many times do you have to remind your child to turn it off? Maybe I’ll rephrase the question….how many times do you have to nag/yell at your child to turn off their tablet? (or does this just happen at my house?) Does your child kindly turn their screen off and easily move on to another activity? Oops, rephrase again…What does your child’s “tablet tantrum” look like?

If your child does easily turn off their screen and calmly refocus themselves on something else, can you please call me? Because I need to know your secret!

I have had many, many parents tell me about how hard it is to get their child to ‘transition from the tablet’ and explain how challenging their behaviors are after the tablet is gone. I’ve witnessed it myself when I tell (okay nag) my kids to turn off their tablets, sometimes ending up grabbing it from them. What usually happens is they scream, yell, or break down in tears. Next, they start fighting. The older one sits on the younger one. The younger one bites the older one. I’m left feeling exhausted and overwhelmed, as well as that good ol’ parent guilt for letting them watch their tablets too much. If this sounds familiar to you, please know, it’s not just you. It’s not just your child.

There’s a reason behind the ‘tablet tantrum.”

When kids are on a screen or tablet, it looks as if they are quiet, sitting, focused, and calm. Actually, what is happening in their brains at this time is the opposite. A number of neurochemicals are required to be in balance in our kid’s brains, and tablets and screen time can disrupt this balance. Video games or other gaming can create a release of dopamine, which feels good for kids, thus they always want MORE. There is never enough.

Next comes an adrenaline response, which is the ‘fright/flight/fight’ response. The brain releases adrenaline which prepares the body’s stress response. Psychological stress can also trigger an increase in cortisol; the stress hormone. Take away the ‘feel good’ dopamine and we see a ‘withdrawal’ effect.

So, we ask a child to turn off their tablet, and what we see is an angry person pumped full of ‘fight or flight’ energy. A tablet tantrum.

Now what?

There are recommendations for screen time. I know things in this world are so stressful as it is, and I’ve definitely given my kids more screen time than I’d like to admit. But I’m trying. We’re all trying.

If you want to check-in and see what is a recommended amount of screen time for your kid, take a look here: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx

Taking away the tablet from your child will usually be hard. But setting limits is important, as there will never be enough screen time if it were up to our kids. Take a deep breath, and remind yourself, that you’re setting limits, you’re doing what’s best for your child by enforcing those limits and encouraging breaks from the screen. If you want to make some changes, your Connecting Dots therapists are there to help you along the way. Remember, we’re all here with you during those tablet tantrums.

http://www.childassessmentandtraining.com/the-ultimate-explanation-about-the-great-screen-debate/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/mental-wealth/201211/screens-and-the-stress-response

Getting the Cooperation of the Uncooperative Child Part 2

By Christine Marchant

There many ways a child will show you that he or she doesn’t want to cooperate. There are many reasons the child isn’t cooperating. Although it may be difficult to figure out why a child is behaving a certain way, it may be counterproductive to make assumptions regarding the motives of his or her behaviour. In the previous post I described how I responded to the volatile child that verbally attacked a CDF (child development facilitator) with everything he had in his skill box. These are the children that are the hardest to love and accept. They tend to push away everyone, which is sad because they really are in need of the love, smiles, hugs, acceptance, and guidance from an adult. In this post, I will describe how I respond to the child that runs away, or darts and hides. These children are difficult to communicate with because they resist by removing themselves from what they see as a threat. These children will refuse to participate in activities and often will climb railings, shelves, counters, tables, etc. Taking these children outside is a HUGE danger!

Communicating with these types of children takes a lot of quiet body and patience. It looks like you are doing what the child wants, but that’s because you are! You need to guide the child to do what you want him to do, and you do this by guiding him towards what he is interested in. If you only provide the activities that you want the child to do, and it’s something that the child loves, you will be able to engage him.

Bringing activities that the child loves isn’t going to be enough for these children because this can lead to them becoming rigid and manipulating you into doing what he wants to do, the way he wants to do it. The point of being a CDF is to be the one in charge of bringing the child along and developing a relationship and maturity. I am always talking about meeting the child on his level. This means going to where the child is always running to. If it’s in his bed, have the session on his bed. If he’s running to the top floor landing overlooking the family living area, you go there. If it’s under the table, you go under the table. I once spent half a preschool morning under a table, lying on my belly, watching the class mates and the child I was with help my hand the entire time. I didn’t make any demands, or have any expectations of him. We laid there watching the other children playing. When you go to their safe place, you will see why he choses it and you will get a better feeling for the ‘why’ he’s doing what he’s doing.

If you are working with children, this is where you start the session. As a parent, you are always keeping this goal in mind. The goal is to keep the child regulated and engaged. You want to continue building a relationship with the child and slowly move him from his safe place to a more functional area. This is the fastest way with the least amount of stress and fuss. This can take thirty minutes up to a month. When I have this type of child, I bring my picnic blanket. I place it in the child’s safe place. This is a bridge between the safe place and the place you are going to be. Change only 1 thing at a time. Change is a stressor for these children. Keep the location and the activity, and change the bridge.

Once the child is comfortable and eager to sit and stay on the blanket doing the activities he enjoys, you start to drag the blanket towards the new spot. Some will drag the blanket back to the original spot. You just calmly say, “It’s ok. It’s only a couple of inches, leave it here.” The child will usually accept it. Once the child is comfortable here, you drag it a couple of inches towards the new spot, and you just calmly reassure him that it’s only a couple of inches and it’s ok. Just keep repeating this. Always keep the activities fun and do what the child is engaged in. Keep the blanket, but the only change is the dragging of the blanket to the new place.

When you are doing this, you must remember that the goal is not the activities. The goal is to keep the child calm, engaged, regulated, and moving to the targeted area. When you finally get to the target area, you change the goal. Now the goal is to move the child up to the next level of play, or maybe speech, or social thinking. At this point, the child is now calm, trusting, and has a relationship with you. Keep the blanket and change the activity. You can do occupational therapy, speech, or just play or read on the blanket. The blanket has now become their safe place.

When the child is now engaged in the targeted goals, you will be leaving the blanket more often for longer periods. Eventually, you will remove the blanket. Sometimes the child notices it, but if you time it correctly, he won’t even notice and eventually, you just stop bringing it. This can be the tricky part. With the blanket gone, you must keep the activities fun and the child engaged. Don’t introduce an undesired activity while the child is transitioning to the new place. Make sure that the child remains calm, which may mean that you drop your expectations or demands on the child. If the child does start to get escalated, it is a good idea to keep his favourite toy or book nearby. It’s also ok to be goofy and make silly faces or engage in a lighthearted way that makes the child feel more comfortable. Regardless of the behaviour, every child is still just a child.

Getting the Cooperation of the Uncooperative Child Part 1

By Christine Marchant

I have been a mother for over 30 years and I ran a private day home for 20 years. I was also a nanny, a child development facilitator for 6 years, and worked one to one with many therapists on many specialized teams for helping children. I have observed that there are many ways a child will show you that he doesn’t want to cooperate. There are many reasons the child isn’t cooperating. In this post, I will list a few ways the child may behave, and a few reasons why he may be using this tactic.

Sometimes an uncooperative attitude or behaviour is anxiety, attention seeking, stress, or previously learned behaviour. We don’t know what is happening inside the child, so we do need to be sensitive to the “why” and not just assume our own reasons for this behaviour. Too often, I hear adults say things like, “oh he’s being bad,” “He doesn’t like me,” “That kid is a BRAT!” or “He’s spoiled!” When an adult thinks these thoughts at the onset of the activity, it taints their approach and reaction to the child. These children tend to get a bad reputation because it’s very hard to work with a child who refuses to cooperate, especially when he is VERY LOUD and negative in this refusal. Some of their behaviours may include yelling, screaming, throwing things, hitting, running away, climbing railings, darting away, knocking things over, hiding, kicking, swearing, or being very passive and just laying there and staring at nothing, or closing his eyes, humming, reading a book, playing with toys and not acknowledging your existence. This is a child’s way of saying that they want you gone.

The child is a child, and he doesn’t even know that he is resisting to cooperate. Often his mouth is being disagreeable, while his brain is saying “What is happening?” This is the vital turning point of the session. When you find yourself locked into a battle with the child, you are at the critical point where it will calm down and go positive or it will completely fall apart. The way you handle the situation will set the tone not only for the session, but actually for the rest of the time you work with that child. You need to take control of the situation and set the tone right away. If you are finding yourself in this battle, drop all expectations. Put your lesson plan away, look at the child, stop talking and just wait. If you have just walked in, just stand silently at the door. If you are in the living room or at the kitchen table, just stop. Don’t put anything away, because this may be a trigger and set the child off. Just slow your breathing, and stand silent. Your body should be prepared for anything, but on the outside, you look calm and passive. Count to thirty and keep your eyes on him! He may throw a toy at you, or dash up, kick you or run away. Answer any questions the child may ask, in a calm quiet voice. Do not use an overly sweet voice because kids see right through it. Just answer normally with as few words as possible. It sounds silly and wrong, but just spend as long as needed in that spot. One day, I spent the whole session standing at the front door. The child threw a fit and ran away screaming every time I showed up. I just stood there, the mom chased the child, scolding and threatening and cajoling, and bribing etc, which just made it worse. When he didn’t get attention from me doing this, he’d greet me with a disdainful “what are you doing here?” This moved into a blatant swearing fest, and saying “I hate you”. I would just sit silent, and he would try to flip the table and throw toys. I continued to remain calm no matter what happened.

Eventually, he would desire my attention. When he reached this point, I knew he was ready for my input. I then printed out my expectations for the session. I also printed out the consequences for the ‘unexpected’ behaviours. This was an older child. He understood natural consequences and the token system. The approach I took with this child is not the same one I use with another child. When working with these children, we must ALWAYS remember that this is a child. A child is a child, and we should not put our life stories onto them. They are not inherently bad or bratty. We stay calm, and allow them to come to us. I honestly don’t know why these children behave this way. I’ve had many of these children in my day home, because these are children that were kicked out of all the other day homes, and the parents hear through word of mouth that Christine takes on the difficult kids. I took in every child, with every type of issue, and I just accepted each one the way they were, an each one was an amazing child. I was also a nanny for years. Now that’s a job! I’ve had a child who sat at the dinner table, looked me in the eyes and put her feet on the table and said “so, you’re the new nanny. I’ll tell you right now, you will not make it to the end of the month, we’ve had 4 nannies fired before you, DON’T unpack your bags” this was said by a beautiful, blond, blue eyed 9 year old girl. I worked there for a long time!

The point that I am making, is to meet the child at their level. This does not mean, that if the child swears, we swear, if he hits, we hit, or if he glares at us, we glare at him. It means that we put our lesson plans to the side, smile, and remain quiet and passive. I tend to do something while I wait. That one session I spent at the door, I literally did nothing. During another session with the same child, I sat at the table taking notes the whole session. I did not chase, follow, or try in any way to engage the child. I did not play with his toys in the hope that he would get curious and join me.

In the next post, I will share with you how I get the younger children who run away to cooperate. The one I described in this post was an older child, who was very volatile, verbally explosive, and aggressive. It took a long time but, my patience won the day. The child was such a little darling and sweetheart once he pushed through his block. The last time I saw him, he was a thoughtful, kind, and polite little boy. I was sad to move on.