The Dance of Service

By Monica Morela, behavioral aide at Connecting Dots

Many scholars within the field of disability studies illustrate the relationship between service providers and families by using different analogies. Yuen (2003) describes how having a child with a disability can be like embarking on a journey to space. Such a quest can be exciting at times, lonely, or scary; and asking for help along the way is always necessary. Alternatively, parents describe having a child with a disability as feeling like a spider sitting on a web (Yuen, 2003). Where weak strands are strengthened by connection, and where a ‘web’ of professionals are there to help. I think that Fialka (2001) beautifully illustrates the professional-family relationship by comparing this connection to a dance. In service provider relationships and in a dance, there is an element of forced intimacy. The nature of our circumstances brings us nose-to-nose with strangers in ways that can be awkward. Being aware of this awkwardness can help behavioral aides and therapists to think about how we can reduce the number of times we step on toes!

Another dimension of Fialka’s (2001) illustration that I found very poignant was the idea of who leads the dance of services. Many practitioners will refer to parents as the experts on their children. It might be more accurate to refer to parents as contributors. In a dance, each individual’s contribution can evolve and build on each other as we offer different perspectives about a child. Finally, in a dance, each partner listens to music that guides the movements of their dance. In the dance of services, ‘music’ can be an illustration of priorities. Priorities for parents and service providers can sometimes differ. This difference can lead to misunderstandings regarding the role and goal of services. When practitioners are willing to put on parents ‘headphones’ they will hear the experiences of parents and will be more effective in strengthening the parent-professional relationship.

References

Fialka, J. (2001). The dance of partnership. Young Exceptional Children, 4(2), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/109625060100400204

Yuan, S. (2003). Seeing with new eyes: Metaphors of family experience. Mental Retardation, 41(3), 207-211. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2003)412.0.co;2

Read MoreThe Importance of Small Talk

By Monica Morela, behavioral aide with Connecting Dots

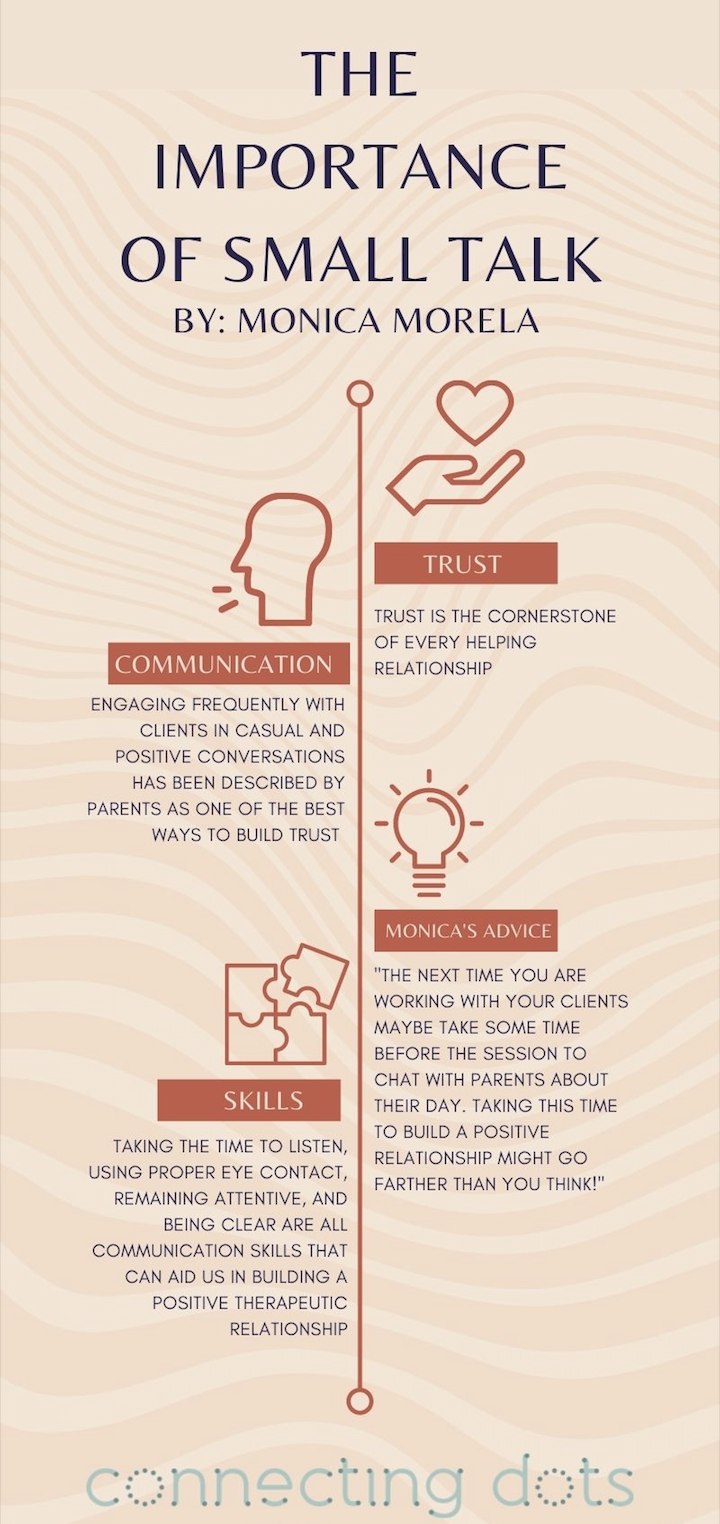

Lynne-McHale and Deatrick (2000) describe trust as being, “the cornerstone of helping relationships” (p. 211). This statement is also corroborated in Reeder and Morris’s (2018) qualitative study regarding the importance of trust in therapeutic relationships. They found that in some cases a positive therapeutic relationship was more strongly correlated with positive treatment outcomes than the choice of what treatments to use (Reeder & Morris, 2018). Reeder and Morris (2018) also found that although professionals are aware of the importance of trusting relationships, they were not always clear on how to achieve a positive trusting relationship with families. So how do we as practitioners and behavioural aides authentically gain the trust of the families we work with? The answer might be more attainable than we think! Francis et al. (2016) examined parent perceptions of best practices for building trust in professional relationships. They found that one of the most important skills for building trusting family-professional partnerships was communication (Francis et al., 2016). More specifically, engaging frequently with clients in casual and positive conversations has been described by parents as one of the best ways to build trust (Francis et al., 2016). This means that our beginning of session chats about the weather and our weekends might be more important than we think! Edwards et al. (2018) provide more detail regarding key communication skills that can help us as service providers build positive working relationships. Taking the time to listen, using proper eye contact, remaining attentive, and being clear are all communication skills that can aid us in building a positive therapeutic relationship.

Lynne-McHale and Deatrick (2000) describe trust as being, “the cornerstone of helping relationships” (p. 211). This statement is also corroborated in Reeder and Morris’s (2018) qualitative study regarding the importance of trust in therapeutic relationships. They found that in some cases a positive therapeutic relationship was more strongly correlated with positive treatment outcomes than the choice of what treatments to use (Reeder & Morris, 2018). Reeder and Morris (2018) also found that although professionals are aware of the importance of trusting relationships, they were not always clear on how to achieve a positive trusting relationship with families. So how do we as practitioners and behavioural aides authentically gain the trust of the families we work with? The answer might be more attainable than we think! Francis et al. (2016) examined parent perceptions of best practices for building trust in professional relationships. They found that one of the most important skills for building trusting family-professional partnerships was communication (Francis et al., 2016). More specifically, engaging frequently with clients in casual and positive conversations has been described by parents as one of the best ways to build trust (Francis et al., 2016). This means that our beginning of session chats about the weather and our weekends might be more important than we think! Edwards et al. (2018) provide more detail regarding key communication skills that can help us as service providers build positive working relationships. Taking the time to listen, using proper eye contact, remaining attentive, and being clear are all communication skills that can aid us in building a positive therapeutic relationship.

I think that we can treat building rapport and trust as a skill. Taking an intentional, conscious, and conscientious approach to providing care will be beneficial for us as practitioners but also for the families we work with. The next time you are working with your clients maybe take some time before the session to chat with parents about their day. Taking this time to build a positive relationship might go farther than you think!

References

Edwards, M., Parmenter, T., O’Brien, P., & Brown, R. (2018). FAMILY QUALITY OF LIFE AND THE BUILDING OF SOCIAL CONNECTIONS: PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS FOR PRACTICE AND POLICY. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 9(4), 88–106. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs94201818642

Francis, G. L., Blue-Banning, M., Haines, S. J., Turnbull, A. P., & Gross, J. M. (2016). Building “Our School”: Parental Perspectives for Building Trusting Family–Professional Partnerships. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(4), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988x.2016.1164115

Lynn-McHale, D. J., & Deatrick, J. A. (2000). Trust Between Family and Health Care Provider. Journal of Family Nursing, 6(3), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/107484070000600302

Reeder, J., & Morris, J. (2018). The importance of the therapeutic relationship when providing information to parents of children with long-term disabilities: The views and experiences of UK paediatric therapists. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518759239

Read MoreWorking with Diverse Families

By: Simran Saroya

Hi everyone!

I wanted to shine some light on a topic I am very passionate about and that is culturally diverse families and what opportunities look like for them. As we work with diverse families and diverse circumstances, we must acknowledge the culture in the homes vs. the culture we may be accustomed to. Western culture is what we base most of our observations and inferences on. What we must understand is that nonverbal and verbal communication looks different across all cultures. For example, eye contact may be an indicator to us that a child is paying attention although in other cultures it may be a sign of respect that they are not meeting eye to eye. It is very important for families, aides and therapists to talk about cultural norms and what that may look like in their household. Another example may be head-nodding for “yes” or “no” answers. In a western worldview, horizontal head-nodding means no, and vertical head-nodding means yes. In other cultures such as Bulgarian, this is completely the opposite. Although most children are accustomed to the western system, it is important to recognize that some may not be and this conversation is important. Lastly, I wanted to share an example of sharing feelings across cultures. As therapists and aides we encourage children to share feelings and express emotions openly while some cultures such as eastern cultures may not encourage speaking about feelings openly.

The biggest takeaway from this short blog post is that cultural norms are very important to understand especially when working with children from many different family backgrounds and dynamics. We definitely understand that all systems in a child’s life are connected and can impact them, but culture is one system that has a huge impact. By better understanding the roles in the home, the child’s needs, the child’s expectations in the house and the parents expectations, we are able to help the children much better.

I found some resources that can help us understand different cultures a bit better when working with children and their nonverbal vs. verbal responses. I will link them down below.

This one talks about eye contact and the differences across all cultures :

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3596353/

This one talks about head nodding and the differences across cultures around the world :

https://www.alsintl.com/blog/interpreting-body-language/

This one talks about emotions:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5381435/

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-03/uoa-wic030508.php

Prezi on Emotions: https://prezi.com/7uqz2kwlrp19/expressing-emotion-east-vs-west/

Nonverbal communication examples:

https://online.pointpark.edu/business/cultural-differences-in-nonverbal-communication/

Read MoreOvercoming fear by providing a therapeutic environment

By: Asmaa Fellah

Starting school (including preschool and kindergarten) is a major transitional event in children’s lives. With transition comes change, and with change comes coping and adapting. For many children, coping with change can be very daunting and intimidating, especially when children have fears. Children are scared of being away from their parents in a new setting and environment. In addition, they are also scared of rejection, meeting new people, and failure.

In kindergarten, many children begin to feel separation anxiety and will start crying, yelling, screaming, and throwing temper tantrums, especially on the few first days. Children are attached to their parents, and therefore feel a sense of securement when their guardians are in their environment. Rather, when children are away from their guardians for the first time and for long periods of time, he or she feels lonely and scared. Not only do they feel scared, but their environment also is completely new to them and they feel lost and overwhelmed. Their sense of securement is instantly gone, leaving them with a sense of fear from their new environment. This is a commonly seen fear amongst kindergarteners.

As children continue in their schooling, expectations and accomplishments are expected from teachers and parents. Homework and assignments are expected to be completed, inside school grounds and outside school grounds. Fear of failure starts to arise as children may be overwhelmed with how much they need to get done, or maybe the difficulty of the tasks, or the pressure of parents and teachers. Fear of failure may prevent them from enjoying school as it will feel forced and unwanted. In addition, children may think that if they don’t meet these expectations and complete their work, a harsh consequence may be set.

The mentioned fears and concepts are applicable to how protentional feelings a child might feel prior to and during an in-home service. Remember, you are a complete stranger to this child and in their point of view, you might be invading their territory. In addition, that child doesn’t have other children around him or her, so they might feel more singled out leading to increased feelings of fear. Now how do we overcome this?

Time and patience. One must understand the difficulty that a child endures when trying to become comfortable and opening up to strangers. In a situation where an in-home aide only has 4 hours, this becomes exceptionally more difficult as it takes longer for the child to become comfortable and adapt.

Second, it is crucial to provide a therapeutic environment that includes the least restrictive environment is necessary for children’s growth and development. A least restrictive environment (LRE) is incorporated in a therapeutic environment. The more negative and unsafe environment, the more children are least likely to learn appropriate behavior to adapt to new environments and events. Proper educational and behavioral support includes an LRE that incorporates a therapeutic and engaging environment, allowing students to prosper and flourish intellectually, emotionally, and socially.

When a student feels safe, he or she is more likely to engage in actions and adventure outside of their confront zone. On the other hand, a student is more likely to present inappropriate actions such as not listening, and engage in inappropriate behavior if the safety component is not presented in their environment. Students use these tactics as a defense mechanism in order to create a sense of safety. A safe environment also creates a sense of welcome and is composed of mutual respect, no-judgment rule. When teachers engage in welcoming actions such as smiling at their students and asking how they’re doing, the students are less likely to be guarded and rather open up and show their true selves. Providing a no-judgment rule allows for students to feel safe to take new opportunities, experiment with new strategies, and engage in new appropriate behavior.

An LRE environment speaks about the accessibility to preferred activities for exceptional students which in turn increases responsiveness to new behavior. Much the same as adults, youngsters have interest and preference which makes them more inclined to complete a task when these are available. Students are also more likely to rebel against the teacher which results in inappropriate behavior if the task is too boring or too demanding. It is important to relate academic and non-academic tasks to the preferences of the exceptional student when possible. When tasks personally relate to the student, he or she is more like to be engaged in the activity. The accessibility to preferred activities also fosters creativity and active learning for these students. Realistically, not all tasks are relatable to different interests nor appeal to students, rather rewarding them after a completed task with an interest of theirs is also effective. For example, a reward for a student who enjoys reading could be ten extra minutes of preferred reading after finishing a math worksheet. Using these techniques increases the chances of responsiveness and participation for all students and can in turn lead to increased active learning.

To summarize, utilizing these strategies allows aides to create a sense of security and welcoming. We all must be patient in regards to children opening up. It is crucial to allow enough time, create a positive atmosphere and allow the child to engage in activities they love. These strategies not only benefit’ the aides but also allows students to take risks and new attempts without feeling embarrassed or afraid.

Read More