Building a Relationship with Everyone Involved

By Christine Marchant

The job description of a Child Development Facilitator is exciting. We don’t know what we’ll be dealing with or what situation we will be entering. By the time we arrive, the entire environment could be in crisis mode. The adults are usually at the end of their ability to cope and are barely able to manage.

I don’t read the IPP or notes on the family or classroom before I start the job because, when I walk in, I like to have a fresh, no bias look at the situation. This is my method, I’m not saying you should do this. You do your own thing to prepare for the job. Everyone has their own style. I love to go in “cold” and observe quietly in the background to see how the interactions are naturally happening.

In this post, I’ll share with you one of my ways of building a relationship with the adults involved.

For about the first two weeks, I stay out of the way.

The first week, I observe the people in the environment, what the children are doing, and how the adults are responding. I always ask the adults involved:

- What are you expecting us to do?

- What three things are the highest priority to you?

- Are you willing to work with me towards these goals?

- Are you open to having me give you the reasons I’m doing something and are you open to following my examples for how to achieve the goals you feel are most important to you?

The second week, I write notes in my book. In the third week, I start addressing the issues. I go over the notes with the adults and ask them if I am going in the direction they are expecting. Some adults dismiss me and aren’t interested in working with me. Most adults though are very open and curious about what I am doing. I’ve met up with some HARD CORE defiant adults, but I don’t get offended. I see these adults as people who are in crisis mode and aren’t able to accept information. Some are exhausted, and have no more energy to receive even a small suggestion. This is ok! I back away and gently build up the relationship between myself and the children. Then, I work on a separate relationship between me and the adults.

About a month into the contract, I usually have everyone on board. As a team, we sometimes get so involved in the child’s needs and our eagerness to “show” everyone we are working hard…we sometimes forget the real reason why we are there. The adults are overwhelmed or exhausted and just nod and agree to whatever the therapists are suggesting. They know and understand that the team knows more. Unfortunately, they don’t always speak up about what they expect and want in their heart. This can lead to the adults not buying into the program and they check out or feel like it’s a waste of time. If they trust you, they will be honest with you and tell you what they really want. That’s the golden ticket!! If the parents don’t plan or can’t envision their child EVER being out of their care, they don’t care about community skills. If the parents don’t see any problem changing diapers, they don’t care if little Bobby ever gets potty trained. If the parents don’t mind doing everything for the child, they don’t care if the child learns self care. As the child grows, the adults grow. When the child starts developing skills, the adults start to realize and understand the importance of the goals the team is creating. Until then? The goals are just words to the adults. As the CDF, we are the bridge between the team and the adults in the child’s environment. By asking the adults what they honestly want and expect, we can start the relationship with honesty.

Sometimes, their desire is really out there. You don’t say anything. You smile and nod. Then you design ALL of your small immediate goals towards the adult’s large goal.

An example of a large goal: “I would really love to be able to snuggle my child and enjoy reading books together”. Don’t focus on potty training, or getting the child to brush his teeth independently, or even community safety. Gear your goals towards “wait for it”, “ ready, set, go” “imaginary play”, “building curiosity”, etc.It’s important that the adults feel heard and are working towards a common goal. This is just one example of a goal that an adult shared with me. The team never knew because the adult never expressed their desire. It was such a large goal for the family, yet such a small thing that everyone else takes for granted.

Another example is the parent that only wanted to be able to open his front door, say to his son “Let’s go to the car”, and finally, to walk together like every other parent and child. This is when I gear all of my goals towards “stop and go”, “wait for it”, “independent play”, “paying attention to his environment”, etc.

Another goal a parent had was to be able to go for a bike ride with their child. I geared my goals towards “look, look, go”, “stop and go”, “find the match”, “match me”, “fast and slow”, “paying attention to their environment”, and “compliance to instructions”.

The adults seldom tell the team these desires because they feel like they should be working on the “real” goals. It’s our responsibility to build a relationship with the adults who are in charge of the child. If the adults feel valued and heard, they will be the best support for you as the CDF. The best feeling ever? When you say to the adults—remember when I first met you? And I asked you what you truly wanted? Well—here it is. Little Bobby is now doing….What is your next most important goal?

It’s actually not difficult to figure out the “real goal”. You take the big final goal, break it down to what mini goals the child needs to do, then break those goals down to micro goals that the child can actually reach. These micro goals will look different for each child. Sometimes, it feels like you’ll NEVER reach the big goal. But it’s okay if you never reach it because the end goal is ever changing while the mini goals are the actual skills that the child is learning and building on. Many micro goals succeeded equals many mini goals accomplished which equals a huge variety of bigger goals accomplished.

When everyone starts to see the micro goals being met, everyone can start to see how we all work together as a team. I have found that when the adults involved start to see how all the mini goals work towards the large goals, they become invested in the adventure. Suddenly everyone is celebrating every micro success and this makes it all worthwhile. THIS is the key to building a relationship with the team.

I love working on teams that enjoy each other’s efforts and ideas. Everyone on the team needs to feel they are important and valuable. I love seeing the parent’s eyes light up when they realize that they can now cuddle with their child or when they can now just open their front door and say “Get in the car!” By the time we get this goal met, the team has a wonderful trusting relationship with everyone involved. We are no longer just strangers coming to their house and telling them what to do. We are a team.

Read MoreTeaching a Child to “Wait for It”

By Christine Marchant

“Waiting for it” is a very important skill for the child to achieve. It’s a developmental skill that comes with the child growing and opening up to their environment and expectations. For those children who are developmentally not able to “wait for it”, we teach this skill slowly and in little steps, just like we teach everything else.

Telling a child to “wait a second!” or “wait a minute!” doesn’t work. If it did, we wouldn’t be in this situation. I like to teach this skill through games.

I pick their favourite game and make “waiting for it” the goal. It doesn’t matter what the game is, as long as it’s their favourite. First, I explain the “rules” to the child. “When it’s our turn, we will count to five before we play.” Waiting will be difficult for the child at first, so start with the lowest number. I like to count out loud. I tap my fingers on the surface of the table or area that the activity is being held. If the child doesn’t understand this, and is still reaching for the activity, I usually place 5 pieces of paper or cards with the numbers 1-5 on it. I flip each card over and say the number. This shows the child time is passing by. The child could still be in the concrete stage and cannot grasp the abstract idea of time passing. I use A-B-C-D-E for the child that is obsessed with the alphabet. If numbers don’t mean anything to the child, use cats, cars, shapes, etc. Anything that catches the child’s attention so they are looking at the cards and counting out the five seconds. We want the attention on the time passing, and they are doing something while waiting.

This is important! Do not make the child “sit quietly” for this target. The target goal is not playing the game or sitting still, it is to recognize that we are waiting for five seconds and this is what it feels like. To show the passing of time, I like to start off with the actual ‘visual’ and ‘audio’ but wean them off of it as they grow and develop. I go from counting out loud, to counting silently. As they develop, I extend the five seconds slowly to as far as 30. Eventually they can watch the timer and by the end of this goal, they know that they are able to transfer this skill to wait patiently to all the other areas.

One of my children a few years ago couldn’t hold still even for five seconds. So, I had him jog in one place for the count of five. Then we moved it to holding the table edge, jumping up and down counting to five. Then it was standing at the table, marching, then sitting on his bum, stamping his feet, etc. Eventually, he was sitting on his chair, rapping out the numbers. It took several MONTHS, but at the six month mark, he was able to wait a full TWO minutes! Quietly with his hands on his lap! At the end of the six months, I would put the timer on for two minutes and he would sit patiently while I “wrote” my notes or “read” my book. I would say, “Here’s the challenge: I’m going to read my book for two minutes and you will sit quietly and patiently.”

This was a very important skill for everyone to learn. There’s a fine line between waiting for your needs to be met, and passively not advocating for your needs. When the child is tiny and learning, we meet their needs immediately. As they grow and mature, we must teach them how to know when to wait and when to advocate for themselves. It is our job to teach and support the child as he is learning to advocate for his needs while learning to wait for his needs to be met.

Another example of teaching this skill is when I had a little boy who was non-verbal and had a global delay. He couldn’t count because he was non-verbal and had absolutely no clue of what we were saying when we introduced him to numbers and letters. This little Bobby was always given whatever he wanted immediately. Little Bobby wasn’t given the skills to manage his frustration or disappointment when he was denied anything he wanted. His behaviour was violent! I worked with him for 9 months and he was finally able to understand “wait for it”. The method I described earlier, did NOT work for him! This little Bobby needed a whole different approach. I’ll share with you how I managed to give him the skill of “wait for it “ in another post.

There are SO many different approaches and styles of teaching. No one way is the correct way and the only way. The most wonderful thing about this job as a child development facilitator is that everyone is allowed to be their own authentic self and interact in their own individual style.

Read MoreResponding Without Assuming Part 2

By Christine Marchant

In the earlier post I explained who I was and shared with you the first 5 things that I hear people say about the children and adults I work with. I explained why I don’t respond to the diagnosis but I respond to the person. Respect, kindness, and compassion—those are the ways I respond to the children and people I work with.

That should always be the go to response—and then you respond to the diagnosis.

Here are another five things I hear all the time. I have been taken to the side and given a “dressing down” for the way I respond. That’s okay—I have my formulas and I know they work—and when they do, I have success. I’m not going to tell you how to do your job. As a child development facilitator (CDF) you bring your own talent and awesome skills to the job. How you do your thing is just as right as the way I do my thing.

I’ll share with you another five things that I hear all the time. Then I’ll share with you why I disagree with it and give an example of how I respond. With that said, I only gave one example of how I respond—there’s a different way for each child and each situation. The way I responded to #4, was only one child. The other dozen of children had a different way. Hopefully over time, I will get a chance to share the different ways to respond to each situation and each child.

- “Always talk calmly and explain everything in short simple words.”

- “If little Bobby gets upset, he’s having a temper tantrum because he’s not getting what he wants. He doesn’t understand why he needs to comply.”

- “Give little Bobby an iPad or iPhone. He can’t understand real life and can’t communicate without the iPad or iPhone.”

- “Let little Bobby eat only what he wants. If he resists or cries, immediately give him whatever he wants.”

- “Be very careful about how you talk to and respond to little Bobby. Autistic people don’t like to be touched or hugged!!!!”

“Always talk calmly and explain everything in short simple words.”

Yes. Use short simple words and talk in a calm voice. BUT!! Not ALL the time!! Use your normal voice and tone. Use hand gestures and talk respectful and kindly. Here is an example. “Little-Bobby-you-must-always-put-your-boots-on-because-if-you-don’t-you-will-get-cold-feet-outside-because-it’s-winter-in-winter-it’s-snowy-…… bla bla bla…” Little Bobby is now ignoring you or is beating on your head with his boots!! I avoid this. I say Bobby sit. Boots on. Line up. Love you. Little Bobby has his boots on and is lined up with his peers and I’m smiling and giving him thumbs up.

“If little Bobby gets upset, he’s having a temper tantrum because he’s not getting what he wants. He doesn’t understand why he needs to comply.”

Little Bobby is not upset because he isn’t getting what he wants. He’s upset because he’s stressing out and has no other way to express himself. He doesn’t know what he’s feeling because the adults haven’t given him the skills to understand the situation and how to respond appropriately. Instead, look at what he is feeling. Why is he feeling like that? I respond by not responding. I stop and try to figure out what is the real issue. Here is an example. The teacher says “Okay, snow pants-jacket-hat-mittens—then your boots. Let’s go! Let’s go!” Little Bobby is laying on the floor SCREAMING. The teacher says, “Stop screaming and put your snow pants on first.” He screams louder. She says, “I don’t care if you don’t want to wear your snow pants, you’re wearing them or you don’t go outside to play.” Little Bobby says, “I’m not wearing them!” And sits in the classroom and watches his peers playing in the snow. She made many mistakes, but I won’t share it here. She said “He always has a temper tantrum when he doesn’t get his way.” I watched this go down—I hold little Bobby until he stops crying. When he’s calmed down to the big sobs, I asked him “What was the problem?” He responds, “Those aren’t my snow pants—they belong to my brother!!” Simple. I acknowledge it. I ask him how he thinks he can solve the problem and we work out a solution. In 10 minutes, he’s dressed in his snow clothes and is outside playing with his peers.

“Give little Bobby an iPad or iPhone. He can’t understand real life and can’t communicate without the iPad or iPhone.”

Constantly handing little Bobby an iPad or iPhone just reinforces his belief that he can’t handle life without it. Little Bobby hasn’t been given the skills to communicate or express himself without the iPad or iPhone. He has always responded to the electronics because the electronics always respond predictably and consistently. There is no reason for him to learn new ways to respond or interact with his environment. I do not like to use any electronics with any child. I establish this rule right at the beginning of my interaction with the children. I take the time to respond to the child and understand him. I start slowly by not getting into little Bobby’s space. I interact very minimally and not directly. I do a lot of side looks and playing beside little Bobby but not insisting little Bobby respond to me. Once he has figured out that I’m way more desirable than the iPad or iPhone, he starts to open up and interact with his environment and leaves the electronics alone. Adults think they need to use the electronics to “reach the child at the child’s level” when it’s actually the complete opposite. Put the electronics away—pull out your inner child and play. Then you are truly at the child’s level.

“Let little Bobby eat only what he wants. If he resists or cries, immediately give him whatever he wants.”

Feeding little Bobby can be a real challenge if you believe this. This is in the same category as the myth of never changing their routine or environment. Little Bobby is like this because the adults have given him the mistaken impression that he can’t handle changes. When we rush around trying to avoid allowing the child to feel any emotions except happy, we are unintentionally reinforcing his belief that he can’t handle changes. Just relax—treat it like everything else. Ask the child what foods they don’t like. Why don’t they like it? Then expose it to them in small doses while playing games or watching a movie. This is when I allow electronics. I put on their favourite 3 minute video and then we eat the undesirable pieces of food. The movie is NOT the reward!! It’s the distraction! Tell them to pay attention to the movie and eat the pieces of food. When the video is finished, ask them “What did you eat?” It’s fascinating. They are surprised. When they are desensitized to the foods, I decrease the video length each time until they don’t even look at the electronics. It’s using the electronics as a tool not a reward. They get stuck in the loop of only eating certain foods and having a meltdown if they are expected to eat undesirable foods because the adults are so concerned that the child can’t handle it.

“Be very careful about how you talk to and respond to little Bobby. Autistic people don’t like to be touched or hugged!!!!”

This is such a silly thing to say. I see a lot of people and children that “don’t like to be touched” so I don’t touch them. By respecting this but allowing them to approach you, and allowing them to lean against you or touch your body with those gentle feather touches, you are respecting them. When you respect them, they want you to touch them or hold them or pick them up. I allow all my children and people to touch me when they are ready. I look distant and act like I am not warm and fuzzy. But I give a lot of winks, small smiles, finger waves etc. So, follow their lead and stop trying to touch and hug children. They will hug you when they are ready.

These are only the first 10 things that I hear so often. I don’t like being aggressive or forceful when I first meet my clients. I don’t see the child as my only client. I see the whole class—the teachers and the assistants and all of the children are my clients. I see the whole family as my client. I like to take the gentle approach and use modeling as my way of getting everyone involved and on the plan towards success. When you hear some information about certain diagnosis and you are told to respond a certain way, stop and say no. Look, listen, feel, and respond to each person as a person first and then the diagnosis. It doesn’t matter what education or experience you have. The only thing that really matters is that you realize that by the time you are in that house or classroom, the entire environment is in crisis mode. Walk gentle, talk softly, and listen to the adults and the children. In another post I’ll share the formula I created years ago, and I follow it each time I start a new case.

Read MoreResponding Without Assuming Part 1

By Christine Marchant

We’ve all been there.

You accept the position of the child development facilitator (CDF). I came from the background of running my own day home for 20 years and over 10 years as a nanny and as a daycare worker. You’d think this was the best experience to prepare me for the job position. No. All the other jobs were easy. I was able to hand pick the families or children I would work with. This job position? I never knew what I was going to encounter.

I’ll share with you some of the tricks I learned over the last 9 years as a CDF. I will say “him” as the gender to make life easy. The word “child“ will refer to all the ages of the people I’ve worked with. I’ve worked with “regular“ kids to anyone with any diagnosis. I tend to not define my clients by their diagnosis—so I don’t respond to them in the way too many people tend to do.

SO many times I’ve been told—

- “Little Bobby has autism—you can not talk to him like the other children.”

- “He doesn’t understand what you are saying- you must talk slowly- after every sentence- stop talking and give him 30-60 seconds to process what you said”

- “Never change the routine or the order of the words because he can’t understand what you mean and it will stress him out.”

- “Autistic children can become violent if they don’t get what they want!“

- “Don’t make jokes!!! Little Bobby thinks you’re serious!”

I can’t tell you how many times I have been given a “dressing down” by therapists, teachers, or a co-worker. Maybe it’s all true. Maybe I don’t know anything. I’m not telling anyone what to do and what to say to the people in your job position. (Note that I didn’t put any diagnosis in front of the word people). I’m only going to share my experience with this job position.

I actually don’t read the IPP or anything about the child I am working with ahead of time. I spend a minimum of two weeks of observation and gentle interaction with the child. After I see for myself the child in his environment, I read the IPP and the notes. I don’t recommend you do this—I do it because I have been working with children since I was a teenager. After graduating grade 12, I immediately went into the childcare center and became a daycare worker. Then a nanny and then a private day home provider. You do your own way of preparing for the job position.

I’ll now explain to you why I don’t believe these 5 suggestions on dealing with little Bobby. I’ll then share how I responded to the child in each example.

“Little Bobby has autism—you can not talk to him like the other children.”

A child with any diagnosis is a child first. Any person with any diagnosis is a person first. Respond to everyone as a person first—then their diagnosis.

“He doesn’t understand what you are saying—you must talk slowly. After every sentence, stop talking and give him 30-60 seconds to process what you said.”

I have seen adults do this to the child. They are so convinced that they are doing the right thing that they start to think inside of themselves and don’t actually look or listen to the child. I am standing there watching the actual facial expressions and the child is just as confused as I am. An example of this—I was working with another CDF from another company in the classroom. This aide was very intense and believed she was very good at her job. She would constantly take me to the side of the room and lecture me on how I am supposed to respond to little Bobby. I was treating him like the other children and I was messing him up! I began to avoid the whole situation. But!!! The child wouldn’t leave me alone!! One time, I was “doing my own thing “ with my child and I heard a little voice say, “Can I play with you guys?” Without lookaying, I said “Sure you can play. Pop in the chair and put your car on the road.” And then I realized it was little Bobby!! The aide charged over to my activity—in front of the child and his classmates and lectured me on how I just made a huge mistake in responding to him like that. The child put the toys down and walked away with the aide. She told him what to do and what to say etc…VERY slowly!! I believe in responding naturally to the child, if they think you think they are capable of handling it, they are actually able handle it.

“Never change the routine or the order of the words because he can’t understand what you mean and it will stress him out.”

This mistaken myth is how the child gets stuck in that loop. The adult is so eager to “not upset” the child that they buy into the idea that he can not handle any changes to his routine or environment. When the adults do this, they are actually setting the child up to think change is NOT okay! When the adults acknowledge that the child cannot change the routine or anything in their environment and they respond to the child with respect, kindness, gentleness, and compassion….. they show the child that it’s okay and that it’s okay to feel like that.

“Autistic children can become violent if they don’t get what they want!“

This is another myth. Children do not become violent if they don’t get their own way. Children become stressed out or very agitated when they feel like their environment is not in their control. It’s not the getting what they want that is the issue. It’s the way they are expressing their stress and fear. The violence is because they aren’t taught that they have other ways to respond. As a baby, flinging themselves around and having a temper tantrum was the only way they had to communicate with their environment. As adults, we must teach the child that it’s okay to be disappointed or upset and then give them the skills on how to appropriately express themselves. If a child becomes violent, don’t respond immediately. Stop, watch, listen, and respond to his feelings—not his words or actions.

“Don’t make jokes!!! Little Bobby thinks you’re serious!”

This one REALLY gets me upset!! Life isn’t that serious! If you respond naturally, you will teach the child that it’s okay to be silly! Make silly jokes! Put the cow on your head and OINK like a pig and hop like a bunny!! Use simple toddler humour to start. If the child becomes upset or confused, stop, assure him it’s okay! This is called “being funny”! Then make a point to be funny twice a session.

These are only the first 5 things I learned while being a CDF. This is a job that takes a lot of flexibility while staying consistent. There’s no one way to respond to each child in each situation. You need to be able to recognize that by the time you arrive in that house or classroom, the entire environment is in crisis mode. The adults are stressed out and not open to new information and new people telling them what to do.

That’s why, instead of reading about the case before I arrive, I try my best to stay out of the way and see what is going on. I allow the adults to get use to my presence. I say nothing about anything. I see how they are coping, and I listen to the adults talking about their stresses and their troubles and their ideas. I stay quiet and I learn how the children behave and how the adults behave. I listen to the therapists, the parents, the teachers, and the assistants, etc. I then read the IPP and look at the whole thing as a whole situation and start asking the adults for their input into the situation. I follow their suggestions. I gently show them the successes and the failures. I then slowly start inserting my way of doing things. I don’t tell the adults what I’m doing or why. I just model it. When I sense they are opening up to be accepting the new information and new ways of doing things, I start explaining as I’m doing. I don’t tell before I do it. I tell as I’m doing it so the adults can see it and hear it and then they can see the results. Once the adults are trusting my skills, I start giving them the responsibility for the decisions of what we do. Then I invite them to model what they have learned and, finally, at the end of the contract, I’m stepping back and allowing the adults to take over. It’s a formula I created years ago. Once I caught on that there’s a formula for success, I wrote it out and started to actually follow it. Now? Every time I enter a new job situation, regardless of if it’s in a school or a home, I follow the formula. It hasn’t failed yet, even though sometimes I don’t get past the first step. But at least I’m consistent and I know that eventually it will be easier.

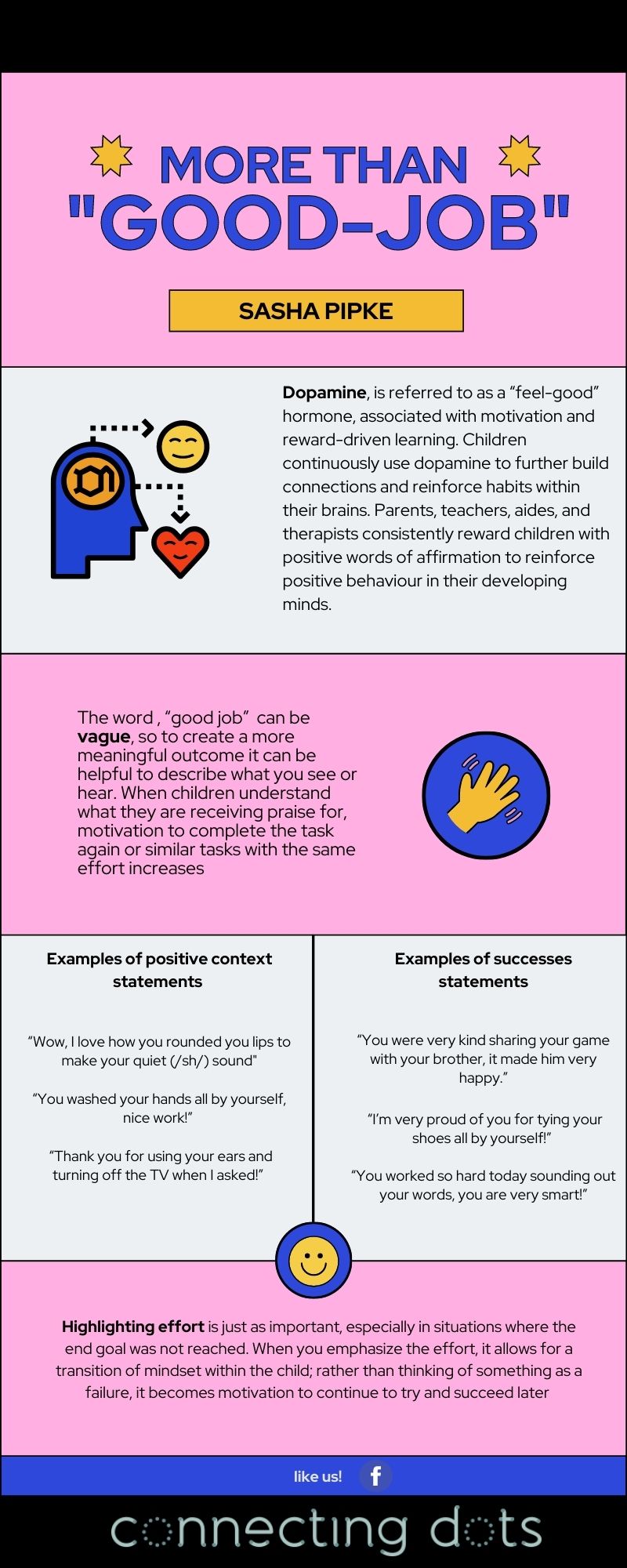

Read MoreMore Than “Good-job”

Verbal Validation for Kids is More Than “Good-Job”

By: Sasha Pipke

Dopamine, also commonly referred to as the “feel-good” hormone is associated with motivation and reward-driven learning. Dopamine allows for a positive sensation released in the brain that motivates future actions, allowing for a similar release of the hormone (Bogacz, 2020). Children continuously use dopamine to further build connections and reinforce habits within their brains. Parents, teachers, aides, and therapists consistently reward children with positive words of affirmation to reinforce positive behaviour in their developing minds. This motivation is known as extrinsic motivation, where the child receives external validation and praise, as opposed to intrinsic motivation (which involves of self-encouragement). The choice of words used by adults plays a critical role in the child’s motivation. We often resort to saying “good job” to further validate the actions of others, yet this phrase is an overgeneralized blanket term, used regardless of the task at hand. Although this seems like the perfect phrase to continue to motivate the child to perform a task, it lacks meaning and does not specifically recognize accomplishments. We must ask ourselves, therefore, how can we change our vocabulary to motivate children in a meaningful way?

As we know, “good job” is ambiguous and vague, so to create a more profound and meaningful outcome it can be helpful to describe what you see or hear. When children understand what they are receiving praise for, motivation to complete the task again or similar tasks with the same effort increases (Schwarz,2018). It’s important to still use vocabulary that the child understands and can easily understand in a positive context. Some examples are:

- “Wow, I love how you rounded your lips to make your quiet (/sh/) sound!”

- “You washed your hands all by yourself, nice work!”

- “Thank you for using your ears and turning off the TV when I asked!”

Additionally, it is important to provide children with the success of their actions. This allows you to provide extrinsic motivation in a way that will allow your child to also feel intrinsic motivation. This can be done with personalized ‘you’ statements that place ownership on the child for their own actions. Some examples are:

- “You were very kind sharing your game with your brother, it made him very happy.”

- “I’m very proud of you for tying your shoes all by yourself!”

- “You worked so hard today sounding out your words, you are very smart!”

Lastly, it is important to highlight the effort, especially in situations where the end goal was not reached. When you emphasize the effort, it allows for a transition of mindset within the child; rather than thinking of something as a failure, it becomes motivation to continue to try and succeed later. Goals do not happen overnight, and children should not expect that everything they do will be accomplished at the same rate.

Saying “good job” has become hardwired to address success in children, however, it does not carry substantial meaning. Changing our vocabulary to better highlight children’s effort and success is a small change that can make the word of difference regarding self-praise and motivation. This change in vocabulary will not happen immediately. Try to first notice in a week how many times you say “good job” then try to replace a few “good jobs” with a specific validating phrase and continue to progress from there. You’ve got this!

References

Bogacz, R.(2020). Dopamine role in learning and action inference. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53262.

Corinne. (2019). Why You Should Stop Saying Good Job and What to Say Instead. The Pragmatic Parent. https://www.thepragmaticparent.com/stopsayinggoodjob/.

Schwarz, N. (2018). 50 Ways to Say “Good Job” (Without Saying “Good Job”). Imperfect Families. https://imperfectfamilies.com/50-ways-to-say-good-job-without-saying-good-job/#:~:text=Author%20Alfie%20Kohn%20talks%20about,reduce%20their%20sense%20of%20achievement.

Read More